“Your Celebration is a Sham”

Slavery, Genocide, and the American “Revolution”

There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour… for revolting barbarity and shameless hypocrisy, America reigns without a rival.

- Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?,” July 5, 1852

Thomas Jefferson’s July 4th 1776 Declaration of Independence (DOI) and the American “revolution” it signified should be taken with a ton of salt. The (DOI) articulated the revolutionary notion that “the people” have the right to dissolve a government that no longer serves their interests and the common good. But who were “the people” in the early U.S. republic? White male owners of substantive property holdings. This left out Blacks, most of whom were branded and ruthlessly exploited as chattel slaves in the new republic. It left out native Americans, reviled as “savages.” It left out women of all races. And it left out much of the white population, which was considered too poor to be trusted with citizenship, though they were welcome to give their lives to fight the British.

Jefferson, whose face is carved into a South Dakota mountain stolen from the great Sioux Nation, is a foul national icon. Henry Wiencek’s volume Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and His Slaves (2012), dug into previously overlooked evidence in Jefferson’s papers and new archaeological work at Jefferson’s Monticello site. Wiencek shows Jefferson to have been a debt-ridden capitalist who took out a slave equity line of credit to build his Monticello estate and who had slave boys whipped in a Monticello nail factory to pay his grocery bills.

Jefferson’s American “revolution” was a proto-capitalist national independence movement led by wealthy landowners, slaveowners, merchants, and elite politicos who feared uprisings from below. These North American exploiters and rulers wanted more breathing space – what Hitler would later call Lebensraum – to preserve and develop further systems of racial oppression, territorial conquest, and class rule.

Listen to this curious, all too rarely noted line in the Declaration of Independence’s list of grievances against King George. “He,” meaning George in the Declaration, “has,” Jefferson wrote, “excited domestic insurrections amongst us and has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions.”

Interesting, no? – a “revolutionary” document that complains about its enemy “exciting domestic insurrection”! A “revolution” driven by fear of “domestic insurrections”!!

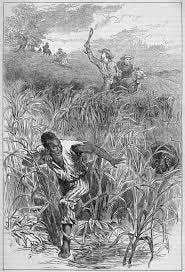

“The inhabitants of our frontiers” – that would that be the original Indigenous First Nations people who the white un-“settlers” from the British Isles and Europe ethnically cleansed from British North America and the early US republic’s eastern seaboard before the US War of Independence. It was not a pretty story. Jefferson’s description of North America’s original inhabitants as “merciless Indian savages” anticipated Orwell by projecting onto Native Americans the genocidal practices that white “settlers” exhibited from day one. Consider the Mystic River Massacre of 1637, part of the Puritan war on the indigenous Pequot nation, one of hundreds of exterminist slaughters carried out by the white skinned Predator as it eliminated Native American peoples from North America between first conquest and 1900. “A force of Connecticut and Massachusetts soldiers,” historian Eric Foner writes, “surrounded the main Pequot fortified village at Mystic and set it ablaze, killing those who tried to escape. Over 500 men, women, and children lost their lives in the massacre,” which included the mass incineration of Indigenous home and families.

The Puritans wept with joy and thanked “God” for helping them flame-broil Indian women and children who stood on ground the “settlers” would turn into a supposed heavenly “City on the Hill.” After a pitiless campaign of removal in which the white (un-) settlers pushed most of the last Indians they had not killed out of New England in the mid-1670s, Foner notes, “the image of Indians as bloodthirsty savages,” Foner writes, “became firmly entrenched in the New England mind.”

That false image, more accurately applied to the marauders and pillagers from England, would prove useful as pretend justification for future genocidal massacres inflicted on the continent’s original inhabitants from the colonial era through the entire 19th Century.

The United States’ first and heralded president, the “father of the country,” George Washington was a determined and vicious killer of Native Americans known to the Iroquois as Conotocarious, meaning “Burner of Towns,” and “Town Destroyer.” In 1779, during the American War for Independence, Washington ordered and organized the Sullivan Campaign, which carried out the genocidal destruction of 40 Iroquois villages in New York.

That blood-soaked butcher is up on Mount Rushmore, along with Jefferson.

Well before the so-called American Revolution was formally announced on July 4, 1776, leading southern slave-owning colonial Independence activists fretted about how the British Empire’s limits on western territorial expansion and Native American genocide threatened to surround slaveowners with too many Black slaves for them to adequately control. Without being able to expand further from the Atlantic coast, they sensed, they and their vicious chattel slave system would be vulnerable to the kind of slave uprisings that were common in the British West Indies. risings. Jefferson’s line about King George supposedly stirring up Indigenous resistance and slave rebellion reflects a central, fundamentally counter-revolutionary motivation behind the American colonists’ decision to break off from England: a sense that the slave system on which North American fortunes depended could not survive except through secession from the British Empire.

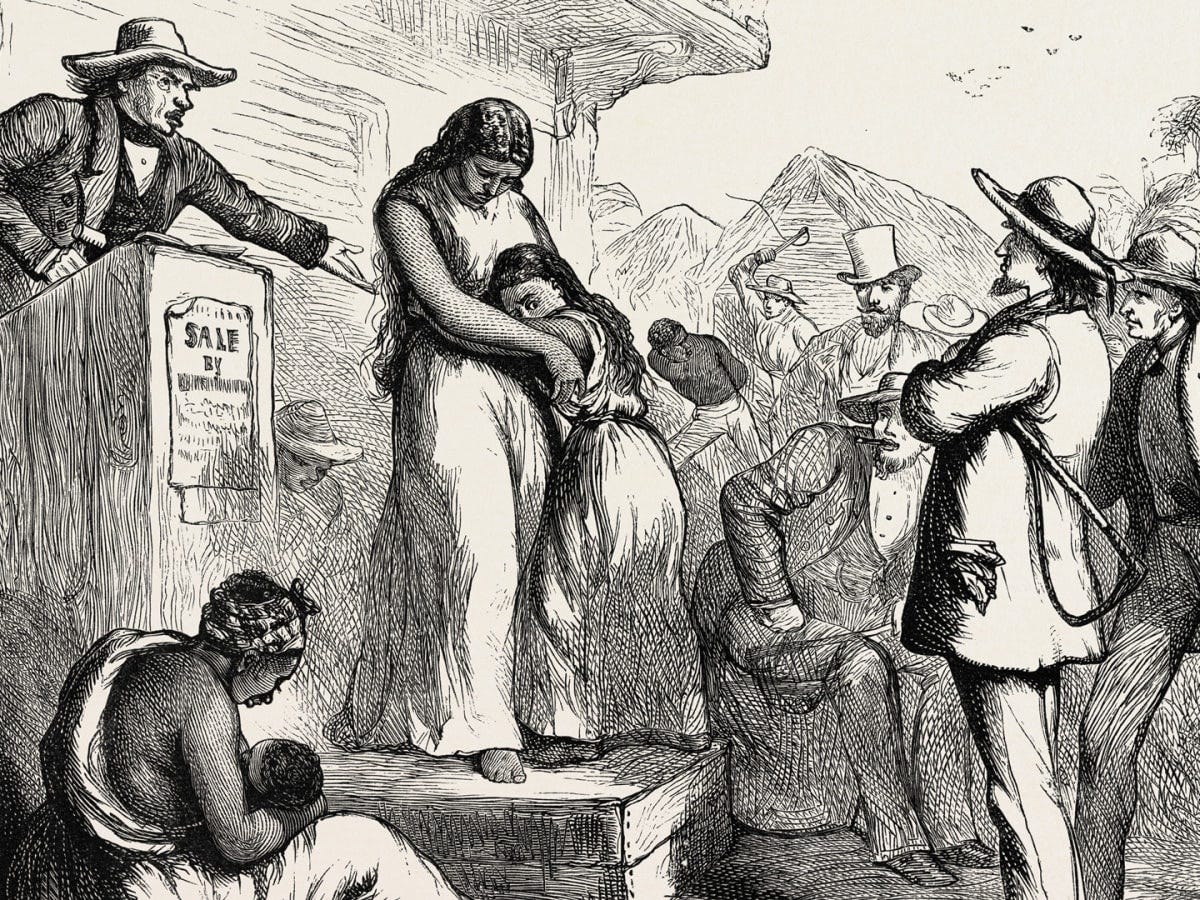

The American “revolution” – that is, the American slave and merchant capitalist break off from England – was a disaster for North American nonwhites. The brutal ethnic cleansing of Indigenous people by the Town Destroyer “settlers” escalated dramatically. The colonists’ triumph over London increased and reasserted slaveowner dominance control over the enslaved Black population, which had been lessened by the with year conflict between the British Empire and the new republic. The North American slave system tightened and expanded in subsequent years. The color line between white and black was drawn with harsher lines than ever before in the so-called land of liberty, as the slaveowners constructed a giant moving frontier of forced labor, rape, and torture camps known as cotton plantations – a Hellish racist regime that moved beyond the Mississippi River, into land seized from Mexico in the name of “Manifest Destiny.”

Seventy-six years after the DOI, the great Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass delivered perhaps the greatest oration in U.S. history, titled “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” By the reckoning of Douglass, himself an escaped slave, the great national holiday was “a day that reveals to [the slave], more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.” Further:

“To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy — a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour…Go where you may, search where you will, roam through all the monarchies and despotisms of the old world, travel through South America, search out every abuse, and when you have found the last, lay your facts by the side of the everyday practices of this nation, and you will say with me, that, for revolting barbarity and shameless hypocrisy, America reigns without a rival.”

Remarkable prose!

To ground Douglass’s eloquent fury in historical-material reality, I can recommend no academic text more strongly than Edward Baptist’s 2014 study The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Rise of American Capitalism. Baptist eviscerates the mainstream academic tendency to see slavery as a quaint and archaic “pre-modern institution” that had nothing really to do with the United States’ rise to wealth and power. In this tendency, slavery becomes something “outside of US history,” even an antiquated “drag” on that history. That tendency replicates a fundamental misunderstanding curiously shared by anti-slavery abolitionists and slavery advocates before the Civil War. While the two sides of the slavery debate differed on the system’s morality, they both saw slavery as an inherently unprofitable and static system that was out of touch with the pace of industrialization and the profit requirements of modern capitalist business enterprise.

Nothing, Baptist shows, could have been further from the truth. Unlike what many abolitionists thought, the savagery and torture perpetrated against slaves in the South was about much more than sadism and psychopathy on the part of slave traders, owners, and drivers. Slavery, Baptist demonstrates was an incredibly profitable, cost-efficient method for extracting surplus value from human beings, far superior in that regard to “free” (wage) labor in the onerous work of planting and harvesting cotton. It was an especially brutal form of capitalism, driven by ruthless yet economically “rational” torture along with a dehumanizing ideology of racism.

The Half Has Never Been Told shows that “the commodification and suffering and forced labor of African Americans is what made the United States powerful and rich” decades before the Civil War. Capitalist cotton slavery was how United States seized control of the lucrative world market for cotton, the critical raw material for the Industrial Revolution, emerging thereby as a nation to be reckoned with in the world capitalist system by the second third of the 19th century.

The returns were wrung through soul-numbing exploitation overlaid with ruthless torture. ‘In the sources that document the expansion of cotton production, you can find at one point or another almost every product sold in New Orleans stores converted into an instrument torture…Every modern method of torture was used at one time or another: sexual humiliation, mutilation, electric shocks, solitary confinement in ‘stress positions,’ burning, even waterboarding…descriptions of runaways posted by enslavers were festooned with descriptions of scars, burns, mutilations, brands, and wounds.”

So Happy July Fourth NOT.

Want a real and actual revolution on the part to ending class rule, white supremacism, patriarchy and all forms of oppression? Check out the a major new declaration from the Revolutionary Communist Party here. If you are in the Philadelphia area, you can still go downtown to join the Recvoms to protest the sham July 4th celebration and call for an actual people’s revolution in front of Constitutional Hall at 1 pm. Here is some excellent background on the rally today: https://revcom.us/en/big-announcement-join-revcoms-july-4-philadelphia-and-nationwide

Another indispensable history

The Counterrevolution of 1776

The successful 1776 revolt against British rule in North America has been hailed almost universally as a great step forward for humanity. But the Africans then living in the colonies overwhelmingly sided with the British. In this trailblazing book, Gerald Horne shows that in the prelude to 1776, the abolition of slavery seemed all but inevitable in London, delighting Africans as much as it outraged slaveholders, and sparking the colonial revolt.

Prior to 1776, anti-slavery sentiments were deepening throughout Britain and in the Caribbean, rebellious Africans were in revolt. For European colonists in America, the major threat to their security was a foreign invasion combined with an insurrection of the enslaved. It was a real and threatening possibility that London would impose abolition throughout the colonies―a possibility the founding fathers feared would bring slave rebellions to their shores. To forestall it, they went to war.

The so-called Revolutionary War, Horne writes, was in part a counter-revolution, a conservative movement that the founding fathers fought in order to preserve their right to enslave others. The Counter-Revolution of 1776 brings us to a radical new understanding of the traditional heroic creation myth of the United States.

It should be added that the British forcibly forbade settlement west of the Ohio River.

I know it doesn't mean much, but every 4th, I listen to James Earl Jones recite Frederick Douglass's speech, and at the end of the day, I burn an American flag.