“There But for a Different Social History Go I”

Middle-class liberals who can’t fathom how a white working-class person might fall for the racist and indeed fascist “great replacement theory” never worked like I did as a red-shirt packaging line employee at the Iowa City Procter & Gamble (P&G) plant in the fall of 2015.

I’ll never forget the 20-something white co-worker who looked aghast at me on his first day of work. “Jesus,” he related, “you’re the only other white person here. Even the team leaders are ni**ers. I’m not taking orders from a ni**er!”

“Nice to meet you too,” I said and walked away.

The Black workers whose presence so bothered him were recent immigrants from the Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The former spoke good English and many of them took Muslim prayers during breaks. The latter spoke French and broken English and showed no signs of religious affiliation. The former workers were taller and more solemn, less playful than the latter. Their skin was lighter, and their features were more angular than those of the workers from the DRC. A good number of the Sudanese men had professional backgrounds. There were more women among the Congolese workers than among the Sudanese.

I enjoyed the shop-floor and break-room company of my Sudanese and Congolese co-workers. I got to work on my lame French skills with a few of my line mates. Some of the Congolese workers were eager to talk to enhance their English. We traded vocabulary. It’s curious how having to don the same lowly unform — blue jeans, steel-toed boots, and red shirts — and perform the same simple and speeded up tasks (filling plastic bottles of shampoo and mouthwash on to moving lines and building pallets at the end of those lines) can break down racial and cultural divisions.

One young worker I spoke with was Rwandan. He kept his distance from the Congolese because, he told me, “I’m a Tutsi and they don’t like me.”

Such cultural distinctions and chances for cross cultural engagement were entirely lost on the racist white worker, of course. The only thing that mattered to him was skin color.

He might have been surprised to learn how sadly critical some of these African immigrants were of US-born Black people, who were sparse in the P&G plant.

The white guy didn’t last long. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t happy to see him go. (The current version of the present writer would have tried to struggle with him about and against his racism; the October 2015 version had no time energy for such things.)

But two things, caveats perhaps, deserve mention here. First, at the risk of sounding religious, “there but for the grace of God go I.” I was immune to the white worker’s toxic racial sentiments not because of some inherent goodness planted in my soul by an anti-racist spirit force but simply because I grew up in a significantly anti-racist and highly educated liberal-left household in Chicago’s most durably and self-consciously integrated neighborhoods (Hyde Park and Kenwood). My folks took me to see Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., speak at Soldiers’ Field in the summer of 1966. I had Black and Asian-American teachers and took years of grade school French at the liberal University of Chicago Laboratory School.

When we picked baseball teams at 59th and Dorchester, we chose on the basis not of skin color but perceived ability and personal friendship across racial lines. (For what’s it’s worth, the Black kids in Hyde Park and Kenwood were as scared as their white kid neighbors of the Black kids who – some displaying knives – came across the Midway from the “ghetto” neighborhood Woodlawn to steal our bikes and baseball gloves and bats. It was an early lesson on how class complicates race.)

Give me a different childhood and family of origin, put me in an all-white small Iowa town where the adults lacked college degrees and worked as prison guards, auto mechanics, truck drivers, and farm equipment salesmen and who’s to say I wouldn’t have become as racist as the white worker I stepped away from.

Line Replacements: From White to Brown to Black (but Not US-American Black) at P&G

Second, while the white racist co-worker I encountered would have had no reason to know it, white workers, historically speaking, were kind of, …well, replaced by workers of color on the lower-end line jobs at the Iowa City P&G plant. I used to run into an old Sixties-era leftist and Iowa City native – a white guy named Jim who regaled me with stories of how those positions were once considered halfway desirable and decent-paying union jobs “for white people.” His mother worked out there for years “and made decent money. She loved it.”

Unions and moderately attractive packaging line wages and benefits had left the plant long ago. Organized labor, collective bargaining, and decent pay for lower end workers were ancient history there – and so were the white line workers who had benefited, however slightly, from the last gasps of the era of mass production unionism. Four plus decades into the savagely de-unionized neoliberal era, P&G had offloaded the hiring and personnel management of the “red-shirt” line workers to a Dickensian temp agency called “Staff Management.” This penny-pinching, mean-spirited company specialized in the employment and abuse of immigrant workers who were desperate to find any kind of minimally safe and remunerative work they could get their hands on.

Before the Sudanese and Congolese influx, it had been mainly Latino and Latina workers on the lines. A P&G supervisor explained to me that the packaging lines were “too close to the floor for many of the new workers from Africa.” They had been built in the 1990s “for short Mexican women.”

Why the previous Mexican and Central American presence on the lines? They worked for less than the white workers since they had fewer options and their often-illegal status meant they had no rights and little desire to stand out and make themselves vulnerable to arrest and deportation by demanding improved conditions.

Why the subsequent and evident shift to workers from Africa? Again there was the usual employer-relished windfall of a fresh wave of recent immigrants whose immediate comparisons were not with the standards of living afforded to longstanding US natives but rather with the horror and extreme deprivation they had recently experienced in their distant and deeply impoverished homelands. Such workers typically have slight interest in resisting their exploitation in US workplaces given the sadly real social and material upgrade they have experienced in moving from the super-oppressed periphery (what we used to call the Third World) of the world capitalist system to the parasitic core of that imperial order. Even poverty near the bottom of the domestic US hierarchy can feel privileged compared to life in sprawling, disease-ridden, and violence-torn “developing nation” shantytowns and in work camps where (as in the DRC) small children toil in mining the raw materials used in making First World cell phones.

But the Sudanese and Congolese presence was about more than that. “There’s too much difficulty with the legal status of the workers from Mexico and Central America now,” the supervisor explained, reflecting on the right-wing nativist politics and policies directed at “illegal” Mexican and Central American workers. “The Africans went through some lottery or something that let them out of their countries legally. They’ve got papers. That means no immigration officers sniffing around, no raids on the plant.”

By this supervisors’ account, the legal predictability of the African workers – the comparative absence of political and legal exposure for hiring them – was profitable enough to make up for the fact that the African workers didn’t feel the same degree of the threat of deportation as workers from Mexico and Central America. (With their superior legal status and the enhanced employability that went along with it, supplemented by good English language skills in the case of the Sudanese, the African workers I spoke with were proud of their ability to refuse work in Iowa’s filthy and dangerous, heavily Latino-staffed meatpacking industry. A number of local Sudanese also owned and operated taxis in town — a viable business before Uber crashed it.)

The supervisor might have added that the African workers didn’t have the “new Jim Crow” felony records that US racist policing and mass incarceration imposes on a shocking number and percentage of Black US-Americans – a racist branding that amplifies the standard racial bias against hiring Black people. During my stint at P & G, which ended in early 2016 (I’ll mention the reasons below), I was struck by the absence of Black US-Americans from the plant even though there was a significant U.S.-American Black population located literally right across from the plant on the south side of Highway 6 on Iowa City’s East Side. Hiring discrimination against people with criminal records and prison histories was certainly part of the reason[1] for this absence (Iowa, by the way, has long possessed the highest rate of disproportionately Black incarceration in the US).

Capitalist Replacement Practice on a Multinational Scale

The owners and investors of P&G couldn’t care less about these kinds of local stories – trifling matters to them – or about the fascistic “white replacement theory” that is trumpeted by the far right in the US and Europe. Many-sided worker replacement is standard practice – no theory required – for great planetary profit syndicates like P&G (1837-20??). The color that matters to such Lords of Capitalist Creation in connection with who they hire and fire (and what, how, and where they invest and organize production and distribution) is green, as in money.

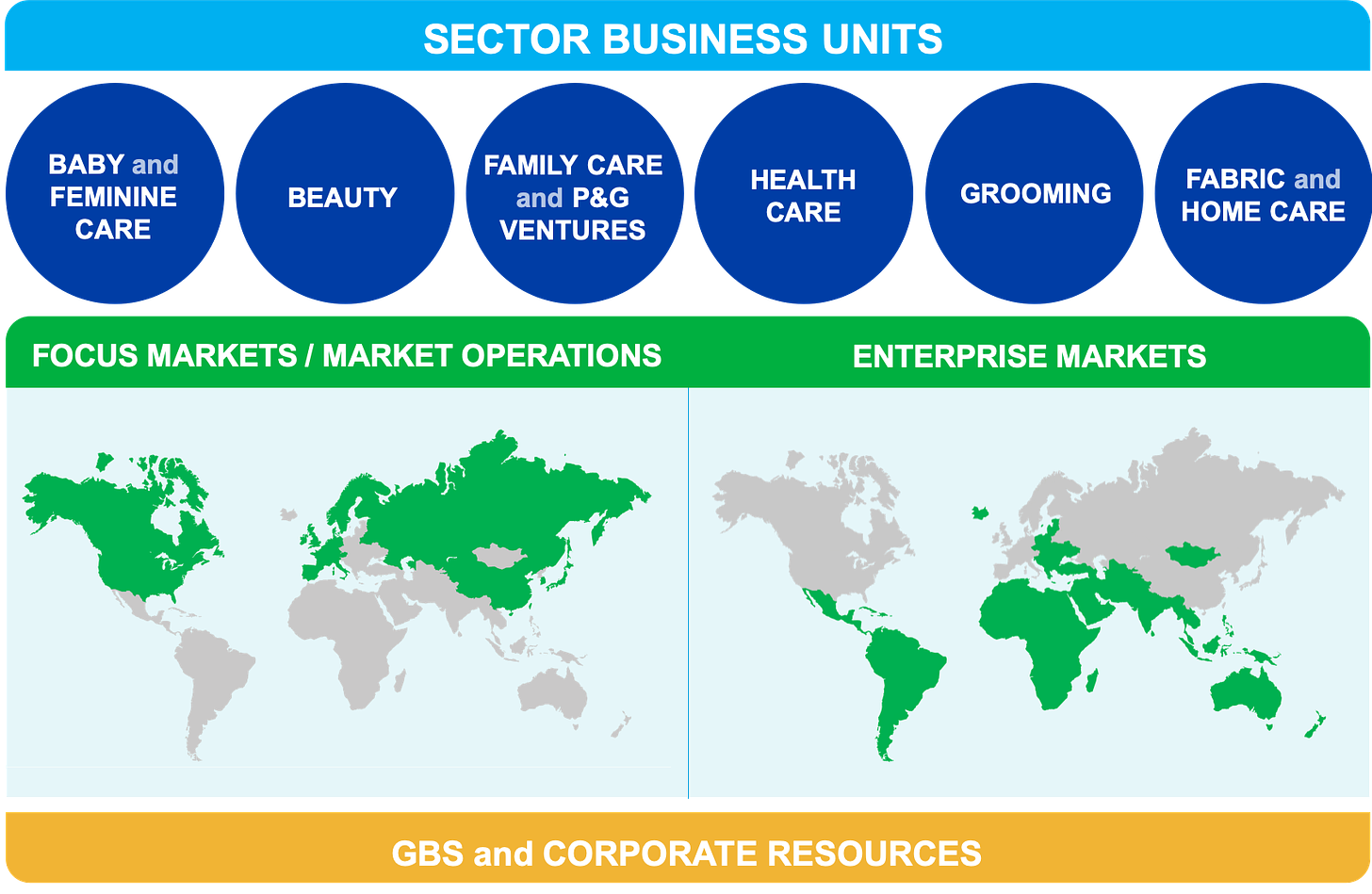

P&G is a $225 billion multinational Fortune 25 megafirm with plants all over the US and in the following countries: Egypt, Israel, Morocco, the Arab Emirates, South Africa, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Columbia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Venezuela, Australia, New Zealand, China, Taiwan, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Pakistan, Philippines, Vietnam, Belgium, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Moldavia, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal Romania, Russia, Spain, Turkey, Ukraine, and the United Kingdom.

Like other multinational firms, P&G regularly replaces one group of workers with another group of workers by shifting capital and jobs from one national and global location to another in search of cheap labor, weak regulations, low taxes, and better access to consumer markets – all understood within the context of its one and only real goal: enhanced return on investment. This is mandated by inter-capitalist competition with other global home, health, and “beauty” product corporations including Colgate-Palmolive, Church and Dwight, and above all the British-Dutch multinational Unilever, which has been outpacing P&G in the “Third World” (Investopedia reports that “Nearly two-thirds of P&G’s revenues are generated from developed markets, while Unilever gets the majority of its revenues from faster-growing emerging markets.”)

If its ongoing and largely successful struggle with other corporations for the biggest possible share of world surplus value (to use the language of Marxist economics) means replacing white workers with Latin American workers – either through hiring the latter within the US or moving production to Mexico – than that’s the move. If it means replacing Mexican, Mexican American, and Central American workers with African workers – either by hiring the latter within the US or shifting some production to Africa – then that’s the move. And if it means replacing African workers with white US workers, then that’s the move.

Two years ago, I ran into another former white P&G worker, a forty-something fellow with an economics degree from the University of Michigan. He told me that the company had shut down seven of its Iowa City production lines and sent the work those lines had done to a giant plant closer to eastern consumer markets in West Virginia. I was intrigued. Sure enough, the Cincinnati Enquirer (the surviving newspaper in P&G’s headquarters city) worshipfully reported the following in the summer of 2018:

“MARTINSBURG, W. Va. — A dozen miles east of Little North Mountain, consumer giant Procter & Gamble has razed an abandoned apple orchard and blasted away 2 million cubic yards of rock. P&G is ramping up operations at a state-of-the-art mega factory that will usher in a new era of efficiency and cost savings….The maker of Tide detergent and Pampers diapers says it is moving its manufacturing strategy toward fewer, larger and more versatile plants. Its mammoth new West Virginia factory – which so far has already prompted plans to close two North American plants and the downsizing of a third – takes P&G's strategy to a whole new level…Just how big is this thing? At nearly 2.5 million square feet under roof, the inside space is roughly the size of The White House, the Sydney Opera House, Buckingham Palace, the Palace of Versailles, the Guggenheim Museum, St. Peter's Basilica and the Taj Mahal – combined. The enclosed area is almost as big as the Empire State Building – except it's mostly on one floor, not 110 stories…P&G's big plan for its big new plant is consolidating a large chunk of production for 11 of its major brands. Built in the eastern panhandle of the Mountain State about 90 minutes drive from Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, the factory is one day's truck drive from 80 percent of the East Coast….Early this year, P&G announced it would close its dish soap factory in Kansas City and downsize most of its shampoo factory in Iowa City, transferring those production lines to West Virginia.”

Hallelujah! In the words of young Karl Marx and his brilliant drinking buddy Frederick Engels in 1848:

“The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionising the instruments of production, and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society. Conservation of the old modes of production in unaltered form, was, on the contrary, the first condition of existence for all earlier industrial classes. Constant revolutionising of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind…The bourgeoisie keeps more and more doing away with the scattered state of the population, of the means of production, and of property. It has agglomerated population, centralised the means of production, and has concentrated property in a few hands…The bourgeoisie, during its rule of scarce one hundred years, has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together.”

Apparently there had been a snag when it came to the West Virginia facility, however. My fellow former P&G worker heard from one of his managerial informants that the corporation was having a problem down there: too many of the white working-class people they were hiring for the relocated production were hooked on opiates. Martinsburg, West Virginia is, it turns “an epicenter of the U.S. opioid crisis.” Maybe that’s part of why some of the work has been brought back to the Iowa City facility.

I don’t recall any Iowa City Congolese and Sudanese workers running a narrative about how evil globalists were “replacing” Iowa’s virtuous and hard-working African workers with drug-addicted southern US whites.

In any event, much of the work has returned. “After announcing two years ago that they would be shifting their shampoo, conditioner, and body wash production lines to a new West Virginia plant,” the Iowa City-Cedar Rapids business class exulted nine days before the murder of George Floyd, “Procter & Gamble has exciting news to share: they’re here to stay.”

No Right to Caucus

The onset of incipient carpal tunnel syndrome (chiefly from the repeated opening of thousands of boxes containing shampoo and mouthwash bottles for placement on moving lines) and the (frankly understandable) absence of any trade unionist sentiment among my African co-workers (who were pleased to have escaped misery and terror in their home countries and happy to be working in a relatively clean and safe factory) compelled my departure from the P&G plant the following February.

I left but not before my position on the second shift prevented me from participating in the much-ballyhooed Iowa presidential Caucus. This supposed grand model of “democracy in action” is unavailable to worker-citizens whose employers do not grant them time off to join with their fellow citizens for two-to three hours to select major party presidential nominees. Thinking I might stand for the proclaimed “democratic socialist” (neo-New Deal Democrat) Bernie Sanders, I brought up getting time off to caucus with Staff Management. The white woman in charge of shift assignments looked at me like I was out of my mind. “Um…no,” she said. Ironically enough, the products my work team was supposed to package (boxes of Header and Shoulders bottles) never showed up on Iowa Caucus night. We were told to go home without pay for a full shift, leading two of my female Congolese linemates to complain about how they had paid for babysitters so they could work that evening. I arrived at the caucus site (City High) too late to participate but in time to watch Iowa City’s right-wing Democratic Congressman Dave Loebsack telling his constituents how important it was to “stop Sanders” and nominate Hillary Clinton. (The Hillary nomination – more on that in a future recollection – sure worked out great!)

“But You are America”

I’ll finish with another darkly comedic story relating to Iowa City, race, and the Procter & Gamble plant. At some point during the second George W. Bush administration, I was confronted by an anxious and disoriented young white man from the Ukraine. He was walking in front of my house just off downtown. He explained to me in broken English that he had just started working at P&G, that he was lost and needed help finding the apartment complex he lived in. I agreed to drive him around town trying to locate his new abode. We kept striking out. “No not this one,” he’d say, looking more distressed.

Finally, I had an idea. I asked him, “where you live, are most of the people Black? Do you see the police out there a lot?” He thought about it for a few seconds, looking puzzled, and aid “yes, most of the people there have dark skin.” And “yes, I often see the police.” I said “why didn’t you tell me? You live out at Dolphin Square apartments on the far southeast side of town, across the highway from the plant where you work.” I drove straight to his apartment complex. He recognized it right away.

It was unthinkable to this young man who had recently arrived from Eastern Europe that what he thought was “free and democratic America” practiced such obvious and extreme residential segregation. He couldn’t fathom that all he had to do was identify the race of his neighbors in a poverty-plagued and heavily policed apartment complex and I knew exactly where to take him.

“But you are America,” he said, “I don’t believe it.”

“Yes we are,” I told him, “and we are racist as all fuck. Stick around and pay attention and you’ll see what I’m talking about.”

Note

+1. So, perhaps, was US-born Black workers’ totally legitimate sense of grievance, rooted in four-plus centuries of savage North American anti-Black racism and racial oppression. The two US-born Black workers I toiled alongside at P&G – both originally from my home city of Chicago – had bitter recollections of racially escalated class oppression in US workplaces and communities going back many years. The Sudanese and Congolese workers I spoke with knew and frankly cared little about that terrible and ongoing US-American history (one of them looked at me like I was crazy when I told him that he and his children needed to beware of white US police officers and that a local sheriff had murdered a young Sudanese man, John Deng, in cold blood in downtown Iowa City in the summer of 2009) and were far too happy about how much better their lives were on the margins of US-American society (where they now enjoyed indoor sanitation and regular garbage removal along with the absence of regular political terror) than in the Hell they had recently escaped (in the war-torn Sudan and the super-exploited DRC) to care about past or present oppression within their new home country

I was born in Iowa City in 1937 and spent my first 13 years there. It had a population of approximately 15000 and was economically dependent on the University of Iowa. It was a idyllic place for early childhood. All that has changed.

Just to let you know: you can add linked footnotes in your Substack dashboard. The option is under the "More" tab at the end of the toolbar.

Great post.