Marx’s Mistakes Were Not at All Disqualifying

Reflections on What it Means to be a “Marxist”

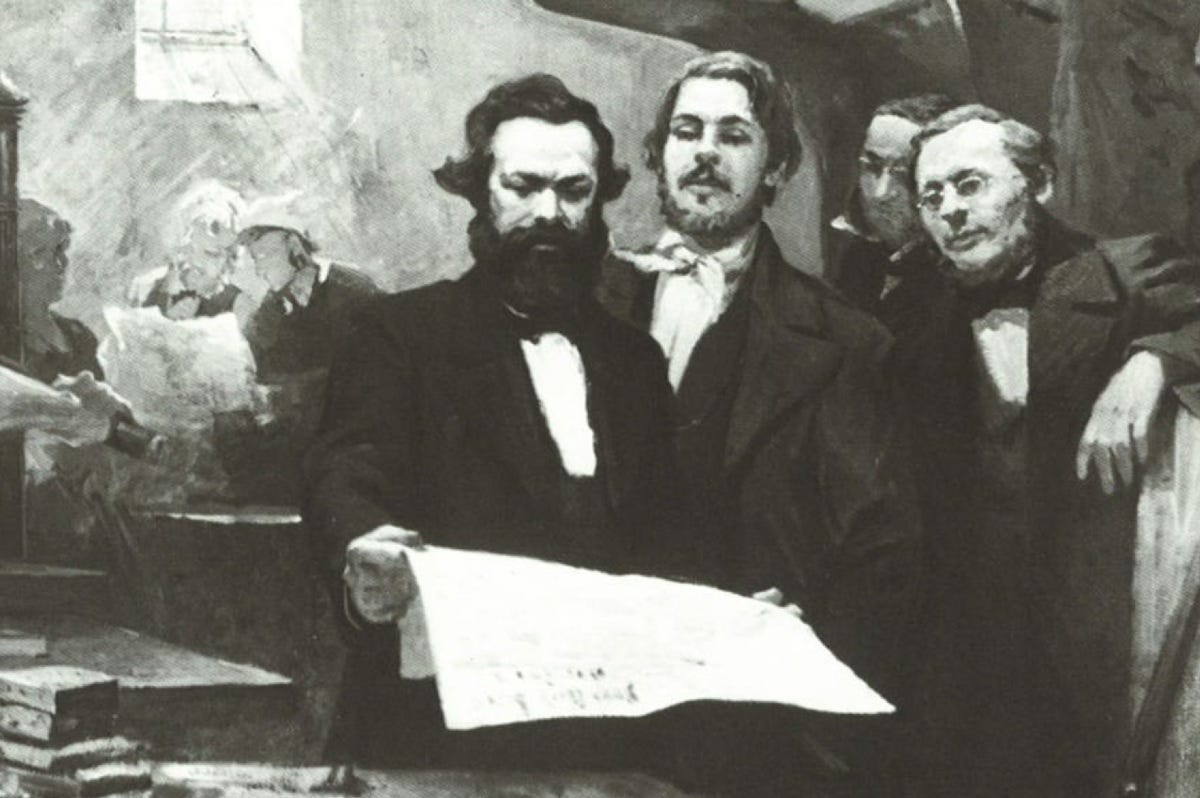

People who identify as Marxists, as I have since before Larry Bird and Magic Johnson first faced off against each other in the NBA, are often accused of being doctrinaire in defense of Marxism’s founders and leaders.

It might surprise some of these accusers to learn that some of us Marxists think that Marx got some big things wrong.

Take Marx’s notion of the proletariat as an inherently revolutionary class destined by historical law to serve as capitalism’s gravedigger. The wage-earning proletariat is no such thing, even though its true liberation would and perhaps will by definition be a revolutionary development for all humanity.

Or take Marx’s related and significantly Western and Euro-centric notion of how and where socialism would develop. The geographic centers of socialist revolution moved outside Europe and its offshoot the United States into the largely peasant-based East, Russia and then China in the 20th Century.

Marx was perhaps over-enthusiastic in his public reflections on the 1871 Paris Commune, which (as he knew) never had any chance of revolutionizing the French nation. The Commune’s leaders fell far short of scientific socialist pedigree and were for the most part caught up in republican and anarchist delusion. And Marx was too willing to sideline his internationalism in deference to the Commune’s claim to be defending the French nation against the Prussians.

Why stay “Marxist” in light of such mistakes, bearing in mind Marx’s own amusing late-life observation that he himself was “not a Marxist.”

Three reasons, the third one being the most important by far.

Understandable and Inevitable Errors

First, the errors I just mentioned were understandable and perhaps even unavoidable given his time and place.

How was Marx not supposed to embrace the secondarily nationalist Commune when artisans, wage earners, anarchists, socialists, and radical republicans had fearlessly seized state power and wielded it as best they could against the treasonous bourgeois government of France? It was the first example in history of representatives of the broad populace taking the reins of government wielding it on behalf of ordinary working people. And it relied to no small degree on its accurate charge that that the French bourgeois government had surrendered radical Paris to the Prussian invaders. Not applauding the heroic Paris Commune would have been a huge political mistake for anyone claiming to be a socialist revolutionary.

It was not a simple situation. As Mary Gabriel notes in her remarkable book Love and Capital: Karl and Jenny Marx and the Birth of a Revolution, “at the beginning of the Paris siege [by Prussian troops with the French bourgeois government in retreat in the fall of 1870], Marx and Engels had warned against revolt, which they said would be utterly futile. By April, however, they saw in the Commune true heroism, and cheered on the Parisians even as they predicted they would lose. ‘What resilience, what historical initiative, [Marx wrote], what a capacity for sacrifice in these Parisians!...After six months of hunger and ruin, caused rather by internal treachery than by the external enemy, they rise, beneath Prussian bayonets, as if there had never been a war between France and Germany and the enemy were not still at the gates of Paris! History has no example of a like greatness.” Indeed.

At the same time, the notion of the Western proletariat as a history-ordained revolutionary class seemed to make a lot of sense in Marx and Engels’ time. It was a very understandable and perhaps unavoidable thing to believe. The British and European working-class movements and struggles of the early and mid-to-late 19th Century and the proletarian movements in the United States after the Civil War (read Bruce C Nelson’s excellent account of radical working-class Chicago in the 1880s ) were extraordinary. They really did seem to beckon the arrival of a new socialist order stretching from Chicago to Danzig.

The Western working class was being significantly remade and expanded during these years. Millions of European artisans and peasants were having their worlds turned upside down by a vicious process of proletarianization and were none too happy about it. They had living recollections of very different labor processes, communities, and lifeways before the oppressive and alienating onset of despotic industrial capitalism, which they confronted and understood as a new and terrible kind of system. Remarkable new working-class uprisings, unions and socialist parties sprung up across the West in response to the new Age of Capital.

The world had never seen such giant concentration of workers as were evident in the new factories, mines, and mills of Europe, England and the United States. It must have all seemed very much like a fulfillment of the prophecy laid out in The Communist Manifesto (1848):

“But not only has the bourgeoisie forged the weapons that bring death to itself [a reference to giant new means of production];it has also called into existence the men who are to wield those weapons — the modern working class — the proletarians…With the development of industry, the proletariat not only increases in number; it becomes concentrated in greater masses, its strength grows, and it feels that strength more…[to the point where] entire sections of the ruling class are, by the advance of industry, precipitated into the proletariat, or are at least threatened in their conditions of existence. These also supply the proletariat with fresh elements of enlightenment and progress.

Finally, in times when the class struggle nears the decisive hour, the progress of dissolution going on within the ruling class, in fact within the whole range of old society, assumes such a violent, glaring character, that a small section of the ruling class cuts itself adrift, and joins the revolutionary class, the class that holds the future in its hands. Just as, therefore, at an earlier period, a section of the nobility went over to the bourgeoisie, so now a portion of the bourgeoisie goes over to the proletariat, and in particular, a portion of the bourgeois ideologists, who have raised themselves to the level of comprehending theoretically the historical movement as a whole….Of all the classes that stand face to face with the bourgeoisie today, the proletariat alone is a really revolutionary class. The other classes decay and finally disappear in the face of Modern Industry; the proletariat is its special and essential product.”

As for the emergence of socialist revolution not in the West but in largely peasant-based nations beyond the industrial and bourgeois-democratic core of the world capitalist system, that was a development reflecting the rise of a new competitive, world-dividing Western imperialism – the new imperialism analyzed (by no means in uniform or always radical ways) by JA Hobson, Karl Kautsky, Rudolph Hilferding, Rosa Luxembourg, and (far more radically) Lenin – that emerged after Marx’s death and provided critical context for World War One (when the leading socialist parties of Europe choose identification with their own national ruling classes in a mass-murderous inter-imperialist slaughter), followed by the Russian Revolution and World War II, followed by the Chinese Revolution. The new imperialism, which both pacified and diverted revolution within the West while exporting it (to speak) to regions and nations beyond the core of the world system, arose shortly after Marx died. Had he lived into his 80s or 90s, Marx would very likely have understood the phenomenon very well and in terms not unlike those developed by Lenin.

(For what it’s worth, Marx near the end of his life seems to have grasped the clear drift towards inter-imperialist war. When a British member of parliament who dined with him at the behest of Crown Princess Victoria in the late summer of 1880 “suggested that European governments might one day jointly agree to reduce their arsenals and thereby lessen the threat of war,” Mary Gabriel reports, “Marx deemed this impossible: competition and scientific advances in the art of destruction would make the situation even worse. Each year more money and material would be devoted to the engines of war, a vicious and inescapable cycle” [1].

Big Qualifications and Corrections to Mistakes

Second, Marx’s mistakes were not without strong qualifications. Marx’s paean to the Paris Commune was only partly tainted by a secondary affiliation with French proletarian nationalism. It remained primarily committed to proletarian internationalism. He sensed correctly at the outset that the Commune was doomed but also saw its bloody repression as an important if tragic lesson of something critical for future revolutionaries to understand:

“it is not enough to lay hold of the old system’s political machinery. Marx summed up that every state was, in its essence, a dictatorship of the dominant class in society…the lesson of the Commune was that capitalist state power has to be smashed and dismantled…it has to be replaced with a new system of state power, the dictatorship of the proletariat….[and that revolution requires] a leadership basing itself on a scientific understanding of what it would take to defeat counter-revolution and what it would take to transform society…to forge a new economy and social system….” (Ray Lotta, “You Don’t Know what You think You Know About the Communist Revolution,” Revolution, No. 323, November 24, 2013, p. 5).

Marx in his later years seriously entertained a “stage-skipping” (so to speak) transition to socialism in largely pre-industrial Russia. He was always keenly aware that Western capitalism depended from it's inception on the imperial exploitation and oppression of people and nations outside the European core.

And while he might have advanced the “inevitabilist” (Ishak Baran and “KJA’”s useful term – see below) notion of the proletariat as a class destined by history to overthrow capitalism, Marx spent countless hours trying to bring science and theory to the working class and wanted bourgeois and petit-bourgeois class defectors to join him in that endeavor. The real-world Marx – the dogged leader of the International Workingmen’s Association – does not seem to have really believed that the proletariat would create socialism without any relevant help from bourgeois and petit-bourgeois class allies and class defectors like himself and Engels. Marx never wrote about the necessity of a vanguard communist party necessarily including revolutionaries from elite classes in the task of enlisting and mobilizing workers as “tribunes of the people” against all oppression – that would fall to Lenin in What is to be Done? (1902) – but two lines in the Communist Manifesto passage quoted above are at least suggestive of the beginning outlines of this comprehension:

a portion of the bourgeois ideologists …have raised themselves to the level of comprehending theoretically the historical movement as a whole.

and especially this:

entire sections of the ruling class are, by the advance of industry, precipitated into the proletariat, or are at least threatened in their conditions of existence. These also supply the proletariat with fresh elements of enlightenment and progress.

(The second line, unlike the first one, involves folks from elite classes not merely rising to the level of the imagined revolutionary proletariat but bringing “down” some of their knowledge – “fresh elements of enlightenment and progress” presumably including a theoretical grasp of history – to the proletariat.)

For what it’s worth, I’ve long thought that Marx’s idea of the proletariat as a class inevitably predestined by historical law to overthrow capitalism was partly propagandistic, by which I mean it was meant to instill confidence in those waging socialist struggle by granting that struggle an air of scientific certitude. This unscientific notion – a form of inherently flawed “political truth” –holds little place in his voluminous journalism, which is loaded with brilliant reflections on a broad range of historical developments shaped by contingency and accident, not inevitability.

Marx’s Core Paradigm Remains Remarkably Intact

Third, Marx’s above “mistakes,” however understandable one finds them, do not meaningfully disqualify “Marxism,” that is, they do not at all falsify the core paradigm in Marx – historical materialism. Here is an excellent synopsis of that paradigm, written nine years ago in a brilliant polemic by the Turkish Maoists Ishak Baran and “KJA”:

“Historical materialism shows that... In order to…continue from one generation to the next, human beings must produce and reproduce the material requirements of life. And for this to happen, people must…enter into particular social relations, especially relations to carry out production. Not just relations of production in the abstract or that people arbitrarily choose – but particular relations of production…determined by the level and character of the productive forces at hand at a given time. On the foundation of this economic base, there arise certain political institutions, laws, customs, and the like, and also certain ways of thinking, culture and so forth. In class society, the class that dominates the production process has forced the rest of society to labor under its command and in its interests. And the class that at any given time dominates economic life in this way has also dominated the rest of society. It controls the organs of political power, most decisively the military forces, and on this basis is able to maintain the broad conditions under which it exploits labor and controls the surplus that is produced – and forcibly keeps the masses of working people in an oppressed state. This continues until the further development of the productive forces of society runs into fundamental conflict with the relations of production. Then a revolution in the political superstructure of society must occur in order to establish and consolidate new production relations that correspond to the new productive forces – and a new dominant economic class, which can organize society to make the most rational use of the productive forces, comes to rule.”[2]

Also useful is Frederick Engels’ following passage from his preface to the 1888 English edition of The Communist Manifesto:

“The Manifesto being our joint production,” Engels wrote, “I consider myself bound to state that the fundamental proposition which forms the nucleus belongs to Marx. That proposition is: that in every historical epoch, the prevailing mode of economic production and exchange, and the social organization necessarily following from it, form the basis upon which is built up, and from which alone can be explained, the political and intellectual history of that epoch…. now-a-days [under capitalism], a stage has been reached where the exploited and oppressed class—the proletariat—cannot attain its emancipation from the sway of the exploiting and ruling class—the bourgeoisie—without, at the same time, and once and for all, emancipating society at large from all exploitation, oppression, class-distinctions, and class struggles.”

There’s nothing about the proletariat being an inevitably or spontaneously revolutionary class, there’s no “class truth” [3] in these succinct summaries of the core Marxist paradigm. There’s nothing either about where or when the first socialist revolutions – where the first superstructural ruptures with the capitalist mode of production – will or should take place. Marx and Engels spoke of socialist and proletarian revolution as something made both possible and necessary by the development of capitalism and as something that was desirable, to say the least. But they also considered it entirely possible that class rule could lead to “the common ruin of the contending classes.” For Marx and Engels, it was up to human beings to act on the great historical tasks and possibilities created by the bourgeois epoch.

Class reductionists and identitarian academics would do well to note Engels’ reference to “emancipating society at large from all exploitation [and] oppression.” That includes gender oppression and racial oppression, both intimately bound up with capitalist class oppression and insoluble under the capitalist mode of production and its attendant political and ideological superstructure. The best pioneering anti-racist and anti-patriarchy scholars (e.g. W.E.B. DuBois and Gerda Lerner) have long understood this and acknowledged a debt to Marx when it came to understanding and fighting gender and racial oppression.

Marx died three years before the first primitive automobile was patented, twenty-five years before the first Ford Model T was produced, thirty-six years before the first nonstop transatlantic airplane flight, forty-six years before the Great Stock Market Crash, fifty years before Hitler’s rise to power, sixty-two years before the first atomic explosion, seventy years before television replaced radio as the dominant broadcast medium in the US, seventy-three years before the first indoor climate-controlled shopping mall was opened to the public, eighty-five years before the first moon landing, one hundred and twenty-one years before the birth of Gmail, and one hundred and thirty-nine years before the rollout of ChatGPT. I find it remarkable how relevant his core paradigm and insights remain to this very day, when we stand on the verge of an artificial intelligence revolution that should horrify us all within the lethal context of capitalism-imperialism — this while the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists has moved its nuclear era Doomsday Clock closer to Midnight than it has ever been. The fundamental Marxian contradictions between social production and private appropriation, between employers and workers, between capitalism and humanity; the deeply alienating and destructive nature of the profits system, which Marx rightly accused of drowning all noble sentiments in the “icy waters of egotistical calculation”; the endless irrational boom and bust business cycle; the endemic insecurity produced by the constant anarchy of capital, the recurrent competition between capitals; the ongoing ruinous enclosure of what’s left of a natural commons by an ever-enlarging and world-spanning capitalism, with its endless “growth”-addicted quest for more cheap raw materials, energy sources, and labor power and new markets; the constant race to new frontiers imposed by the tendency of the capitalist rate of profit to fall; the recurrent creation of speculative bubbles created by parasitic surplus capital lacking profitable productive investment; the regular cringing subordination of the dominant political, intellectual, and media culture – the superstructure – to the needs of those who own and control society’s material productive base and commanding financial heights…all this and more that Marx analyzed and denounced are every bit as evident today as they were in the mid-to-late 19th Century. The core Marxist paradigm is validated. And the basic Marxist choice between (a) “the revolutionary reconstitution of society at large” or (b) “the common ruin of all” is more starkly and urgently posed today than ever before thanks to the escalating and grave ecological crisis that fossil fuel-addicted, expand-or-die capitalism has created since the end of World War II. The “emancipat[ion of] society at large from all exploitation, oppression, class-distinctions, and class struggles” has now become an existential life-or-death issue for the human species.

Postscript: Mary Gabriel’s book makes it clear that Marx impregnated his housekeeper Helene Demuth, fathering a child that Engels falsely claimed to have parented. Certain religiously inclined folks and/or feminists I know will fasten upon this transgression as if it somehow discredits Marx’s scientific and revolutionary work. Such fixation and reflexive denunciation is an all-too common, disastrous, authoritarian and debate-killing practice in contemporary liberal and “left” cancel culture.

Endnotes

1. Queen Victoria's daughter, wife of the future German emperor, was concerned about big bad Marx and so asked her friend and British Parliament member Sir Mountstuart Elphinstone Grant Duff to check “the Moor” (as Marx was known to some his friends) out. Duff invited Marx to join him at his club “the Devonshire” and the two men talked amiably for three hours. "When Duff asked how Marx could expect the German military to rise up against its government,” Gabriel writes, “he pointed to a high suicide rate in the army and said the step from shooting oneself to shooting one's officer was not long." Gabriel, Love and Capital, pp. 473-74.

2. Ishak Baran and KJA, “Ajith – A Portrait of the Residue of the Past,” Demarcations: A Journal of Communist Theory and Polemic, December 2014. This is a remarkable elucidation of historical and dialectical materialism in the context of defending the Revolutionary Communist Party USA and its leader Bob Avakian against a militantly subjectivist, religious, “inevitabilist,” and reactionary attack from the Communist Party of India’s mis-leader “comrade Ajith.” Two terms I use in the present essay – “inevitabilism” and “political truth” – are taken from Baran and KJA.

3. See Baran and KJA, “Ajith,” pp.16-33, for a critique of “class truth” mythology in past and contemporary communist thought. As Baran and KJA note, “comrade Ajith” falls prey to “the incorrect idea that truth has a class character,” reflecting the preposterous notion that “whether something is true or not depends on, or is conditioned by, the class or social background or political stance of the person (or social grouping) who holds, advances, or argues for particular views.” This is a “proletarian” version of the deeply flawed subjectivist bourgeois “standpoint epistemology” that pollutes so much Western academic “postmodern” and identitarian thought with the openly childish notion that there are “many interpretations of reality…none of [which] can legitimately claim to represent objective reality” since “there is no objective standard” and “you have your truth and I have my truth,” scientifically determined reality be damned. A critical corrective text here is the prolific British Marxist and Soviet historian E.H. Carr’s classic volume What is History?

Fantastic piece, well done. For whatever flaws he had, it remains that any view of history and the current social arrangements we have is incomplete without a Marxist analysis.

Thank you Paul, for a concise incisive exploration of Marxist thought evolution. As we struggle to be keepin' on, this is the type of analysis. that is so desperately needed.