One of the many indications that Donald “Sweep Out the Marxist Vermin” Trump and his followers are fascist is their recurrent preposterous[1] “accusation” that the militantly capitalist and imperialist Democrats are Marxists.

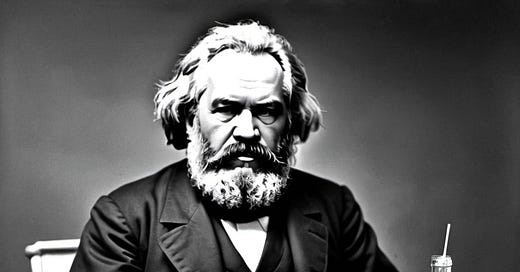

I put the word “accusation” in quote marks because I don’t share the view that there’s something terrible about being a Marxist. I’ve been a Marx fan for damn-near half a century, ever since I first read Karl Marx and Frederick Engels’ famous 1848 The Communist Manifesto in an undergraduate political science class where that remarkable document was assigned by a right-wing Czech émigré who considered reading it necessary “so as to better know the enemy.”

I loved “the enemy.”

Ever since that time and a couple of subsequent classes I took with Marxian historians, asking me if I was a Marxist has been like asking me if I speak English.

Which raises an interesting question: what does it mean to be a Marxist?

Let’s start with some things it doesn’t or shouldn’t mean

Three “Mistakes”

Being a “Marxist” should not mean treating Marx’s words as holy scripture. It doesn’t mean religiously accepting every concept in Marx’s analysis, regardless of its concordance or lack thereof with evidence.

In his brief graveside speech after Marx’s death, Marx’s longtime collaborator Frederick Engels hailed his great intellectual and revolutionary partner firstly as a “man of science” and the developer of “historical science.” People committed to scientific inquiry and method do not cling to theories and explanations that do not match objective reality.

Here are three things in Marx’s naturally timebound interpretation of history that have not stood the empirical test of historical time:

(i) Marx’s notion that the wage-earning proletariat has an “inevitable,” structurally produced “standpoint,” an “historical mission” that make it destined to be the revolutionary “grave-digger of the bourgeoisie” (of the capitalist class and system). This perspective permeates The Communist Manifesto, where the young Marx and Engels wrote the following:

“If by chance [lower middle class people] are revolutionary, they are so only in view of their impending transfer into the proletariat, [whereupon]…they desert their own standpoint [for] that of the proletariat…. The development of Modern Industry…cuts from under its feet the very foundation on which the bourgeoisie produces and appropriates products. What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own grave-diggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable” (emphasis added).[2]

This idea was not prevalent in the mature Marx’s more scientific writings but it reappears in his magnum opus Capital [3]and in his rapidly penned defense and analysis of the 1871 Paris Commune, The Civil War in France, where he referred to Communism as “that higher form to which present society is irresistibly tending by its own economical agencies” and as the “historic mission” of “the working class” (emphasis added).[3A]

(ii) Marx’s notion that capitalist industrialization was driving humanity towards a harsh polarization between just two classes: an ever-smaller bourgeoisie and an ever-larger mass of exploited proletarians.

(iii) Marx’s idea of the history of pre-capitalist society as moving through linear and teleological stages progressing from primitive communism to slavery to feudalism to capitalism.

The third “mistake” does not concern us here. It has been exposed by historical and anthropological data unavailable to Marx during his many years in the British Museum[4].

The first two “mistakes,” not without considerable qualification, were understandable in the time during which Marx wrote – when millions of working-class people (including masses being turned from artisans and agrarian smallholders into first-generation proletarians) rose up against the “Dickensian” and Zola-esque horrors of a new and rapidly expanding industrial capitalism in England and Europe. They were shot down by the history that unfolded after Marx died.

A critical part of that post-Marx history was the transition from “the Age of Capital” to “the Age of Empire”[5] – the rise of capitalism-imperialism in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. As the great Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin observed in 1916, capitalists in the rich Western nations (what was later called the “developed world” and “First World”) exploited workers in the impoverished global periphery (the “developing world”), where wages and materials were much less costly. The enhanced profits resulting from exploitation of what later became known as “the Third World” permitted rich nation “monopoly capital” to boost real wages in imperialist home states, producing a “core state” working class far less inclined to proletarian revolution and international solidarity. The new capitalism-imperialism pre-empted the extreme internal class polarization that Marx had seen as inexorably marching Europe and the United States towards socialist revolution and communism. At the same time, post-Marx capitalism developed a considerable new professional middle class that did not fit Marx’s two-class model.

As the revolutionary communist leader Bob Avakian writes in his essential document Breakthroughs: The Historic Breakthrough of Marx and Further Breakthroughs with The New Communism (Chicago: Insight Press, 2019):

“some specific predictions made by Marx and Engels by observing the tendencies in capitalist society during their lifetime, in particular that capitalist society would continue to be more and more divided into two antagonistic classes—the bourgeoisie (capitalist exploiters) and the masses of exploited proletarians—with the middle class shrinking, have not been borne out, particularly with the further development of capitalism into an international system of exploitation, capitalist imperialism, involving the colonial plunder of the Third World and the super-exploitation of vast masses of people there, in a global network of sweatshops. Bourgeois critics of Marxism (such as Karl Popper) have seized on the difference between the predictions of Marx (and Engels), about the polarization in capitalist society and what has actually taken place there, with the development of capitalist imperialism, to attempt to discredit Marxism and its claim to be scientifically valid. But such ‘critics’ ignore, or seek to dismiss, the scientific analysis, begun by Engels toward the end of his life (toward the end of the 19th century) and carried forward by Lenin, of how colonial depredation by capitalist imperialism has provided the spoils which are to a significant degree the material economic basis for the bourgeoisification of a section of the working class and the growth of the middle class in the ‘home countries’ of imperialism, including such countries as England and then the United States as the leading colonial (or neo-colonial) power, with a vast empire of exploitation.”[5A]

Within the vast population of employed people under the capitalism system that has developed since Marx died, moreover, a considerable minority “may not own means of production, per se, but [are] possessed of …rare skill[s] [that permit them] to command a lot of remuneration…[and] people who generally have acquired a high level of education, people in the professions for example, also are in a different position than people who own no means of production and have no highly developed skill… people in the professions and similar situations, along with the owners of small-scale means of production (or small-scale means of distribution, like a small store owner or shopkeeper) make up the middle class (the petite bourgeoisie) as opposed to the big bourgeoisie, the capitalist ruling class.”[5B]

Neither in its imperial core nor across its vast periphery has capitalism-imperialism created the two-class society imagined as the prelude to imminent proletarian-majoritarian revolution imagined in The Communist Manifesto and Capital.

Twelve Scientific Truths

Do these timebound (and arguably also place-bound) “mistakes” invalidate Marxism?

No! They do not since neither of them undermine Marx’s core scientific contributions to understanding and changing the world and history on that path to human emancipation.

I count twelve core living and richly validated contributions in Marx’s “historical science” and revolutionary politics 141 years after Marx’s death:

1. An understanding of historical eras as rooted in and defined by underlying modes of material production, with those modes understood as combining technical forces of production with social relations of production and as providing the economic base for political and ideological superstructures conditioned and constrained by those material foundations[6]. As Marx and Engels explained in The German Ideology (1846): the "ruling ideas" of an epoch (such as the unscientific bourgeois idea that “human nature” is inherently acquisitive, selfish, competitive, and, basically capitalist) are those of the ruling class that stands atop its productive base: "the ideal expression of the dominant material relationships, the dominant material relationships grasped as ideas.”

2. Understanding the capitalist system not as the economic end game of homo sapiens’ societal existence and “human nature” but rather as a vicious and historically specific form of class exploitation and class rule resulting from the generalization of commodity production, the separation of the working population from ownership of the means of production, and the working majority’s employment as wage-earners producing surplus value (see below) for capitalists who own the means of production as private, profit-seeking property that is embroiled in competition with the other capitalists for shares of total surplus value realized through the sale of commodities. “Modern” capital, Marx showed, was a social relation, It stood atop a particular and transient historical regime of class oppression and exploitation.

3. The discovery of surplus value – the difference between the amount of value that wage-earners produce for their employers and the commodity value of (and hence wages paid for) their labor power – as the key source of capitalist profit.

4. Uncovering key tendencies and laws of motion inherent in the capitalist mode of production: mechanization and subdivision of tasks in the labor process; the concentration and centralization of capital; the polarization between extreme wealth at the top and extreme misery at the bottom of society; the recurrent tendency for the overall rate of profit to decline; recurrent cycles of boom, speculation/financialization and bust, “commercial crises” and financial implosions followed by material re-expansion; a systemic “expand-or-die” requirement for overall growth; the rape and spoilation of the natural environment (as well the human spirit); the constant driving of all this and more by the competitive war between capitals for the greatest share of total surplus value/profit.

5. Identifying the core contradiction of capitalism as the conflict between ever more highly organized social production and the anarchy of private appropriation. Many if not most folks who identify as Marxists think the primary capitalist contradiction is the class polarization and struggle between labor and capital.[6A] A careful reading both of Marx’s political-economic works and of capitalist history demonstrate otherwise. It shows that “the anarchy of capital,” the conflict between organization and anarchy (at bottom a contradiction between the forces and relations of production) is both the system’s top driving contradiction and the critical material-historical context for labor-capital class struggle.[7]

6. Grasping the (bourgeois) “democracy” that capitalism advances as a superstructural cloak for capitalist class rule – as an outer and dispensable shell of illusory popular sovereignty around the underlying “dictatorship of the bourgeoisie,” itself rooted in the private competitive and for-profit ownership and command of the mode of production (“the dominant material relationships”).

7. Marx’s understanding of the profit-driven capitalist labor process (the capitalist division of labor) as fundamentally dehumanizing and alienating.[7A]

8. Internationalism – an understanding that proletarians “have no country” combined with opposition to “the exploitation of one nation by another.”[8]

9. Rightly insisting that a sweeping socialist revolution – what Marx called not “democracy” but rather “the revolutionary re-constitution of society at large” (Marx and Engels, The Communist Manifesto [1848]) and indeed “the dictatorship of the proletariat” (Marx, Class Struggles in France [1852]) – was required to avert catastrophe and lead humanity beyond the exploitative, oppressive, environmentally disastrous, and anarchic capitalist system and towards a future worthy of its species being – to a world where no part of humanity exploited any other part of humanity and where the reigning maxim was “from each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs” [9] Marx correctly stipulated that this revolution must seize state power, purge capitalist state institutions, radically refashion the state, and wield state power with great, unreluctant authority to transform society all the way down to the mode of production and back up to the superstructure.

10. An understanding of socialism – “the dictatorship of the proletariat” – not as “democracy” or the final abolition of classes but rather as a transitional stage in which the proletariat is the new ruling class and during which society transcends “the conditions for the existence of class antagonisms and of classes generally,…thereby abolish[ing the proletariat’s] own supremacy as a class.” [10] In 1871, Marx pointed out that the transition to communism would involve “long struggles,…a series of historic processes, transforming circumstances and men.”[11] He saw “no ready-made utopias to introduce par decret du people” [12]to create a world beyond “the exploitation of one part of society by the other”[13] and “the exploitation of one individual by another”[14] a world in which “the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all” and the reigning maxim is “from each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs”[9] (Marx’s language made it clear that he was morally opposed to any and all forms of exploitation and oppression past, present, and future and not only capitalist class exploitation and oppression).

11. An understanding that the alternatives to the “revolutionary re-constitution of society at large” along socialist and then communist lines was “the common ruin of all.”[15] This stark choice that Marx and Engels posited between liberating revolution (“revolutionary re-constitution”) or collective collapse (“common ruin”) has never been more graphically borne-out than it is today, with anarchic Doomsday capitalism now pushing humanity ecology into potentially irreversible climate catastrophe, epidemiological crisis, fascism, and nuclear war. Its “revolution, nothing less” or the final cancellation of all prospects for a decent future.

12. Understanding the need for a communist cadre to inspire and lead masses to revolution. This last point might seem surprising given my above discussion of Marx’s “mistakes.” But…well, it’s complicated. While Marx seemed in many of his writings to think that the revolution we need was the inevitable, almost natural outcome of the capitalist contradictions he analyzed, most particularly of the emergence of a giant proletariat destined to “expropriate the expropriators,” he also demonstrated a lack of faith in any inevitable laws of history the proletariat and humanity to communist emancipation. He spent most of his time outside the study haranguing his fellow Europeans, workers included, on the need to get their shit together and make an actual revolution for the emancipation of the proletariat and thereby of all humanity.

The Communist Manifesto was a political pamphlet intended to instruct and inspire the working class. Its existence assumed by its very nature that development of revolutionary class consciousness on the part of the proletariat was NOT inevitable; if such consciousness had been inevitable, why would the Manifesto have been written and why would the bourgeois class traitors Marx and Engels, and their compatriots have formed the Communist League in 1848?

On the final page of the Manifesto, Marx and Engels say that the “the Communists [members of the Communist League]…never cease, for a single instant, to instill into the working class the clearest possible recognition of the hostile antagonism between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat” in Germany.[16]

A passage from the mature Marx suggests something rather different than revolutionary proletarian class consciousness as the outcome of capitalist development. Marx wrote in Capital that capitalism brought “Accumulation of wealth at one pole of society [that] is therefore at the same time accumulation of misery, agony of toil, slavery, ignorance, brutality, and mental degradation at the opposite pole.”[17] Ignorance and mental degradation are hardly the stuff of revolutionary class consciousness.

As Engels noted in his graveside speech, “Marx was before all else a revolutionist. His real mission in life was to contribute, in one way or another, to the overthrow of capitalist society and of the state institutions which it had brought into being, to contribute to the liberation of the modern proletariat, which he was the first to make conscious of its own position and its needs, conscious of the conditions of its emancipation.” An interesting formulation. Engels’ phrase “in one way or another” somewhat suggests that Marx was open to different pathways to revolution than proletarian class struggle alone – something suggested by Marx’s late-life musings that Russia might make a contingent transition to socialism in part via peasant communalism. Engel’s phrase hailing Marx as “the first to make [the proletariat] conscious of its own position and its needs” shows that Marx did not believe that proletarian class consciousness was actually inevitable or likely to develop without the assistance of class traitors from the bourgeoisie and petit-bourgeoisie like himself. Marx would have understood and approved of his fellow class traitors Lenin, a fierce critic of bowing to the economistic and nationalist spontaneity of workers and trade unionism, and Mao, the communist leader of a peasant-based revolution, leaders of great socialist revolutions in a time when communist-led revolution had moved beyond the core states of the world capitalist system, where key segments of the Western working class had been bought off by imperialist super-profits.

In The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels reference “sections of the ruling class” who are knocked down into or near the proletariat “by the advance of industry” and “supply the proletariat with fresh elements of progress and enlightenment.” Marx and Engels noted the existence of “bourgeois ideologists who have raised themselves to the level of comprehending theoretically the historical movement as a whole.”[18] Here Marx and Engels were referring to themselves and other early communists from bourgeois backgrounds, who would not rely on supposed iron laws of historical inevitability alone as the key to socialist revolution.

Please report any typos or other errors in comments or via email.

Notes

1. I’ll stand corrected if anyone can produce evidence of Chuck Schumer, Barack Obama, Adam Schiff or Nancy Pelosi (or fill in your big-name Dem) calling for a mass popular uprising to establish a dictatorship of the proletariat that puts humanity on the road to a classless society in which the reigning maxim is “from each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs.” These and other top Democrats have long proved themselves to be dutiful servants of the capitalist ruling class and (more importantly) system that Marx loathed.

2. Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, The Communist Manifesto (New York: WW Norton, 1988), pp. 64-66.

3. Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. 1 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1977), pp. 713-15.

3A. Karl Marx, The Civil War in France (Peking: Foreign Language Press, 1970), p. 73.

4. See Paulo Tedesco, “How Marxists View the Middle Ages,” Jacobin, April 18, 2022, https://jacobin.com/2022/04/marxism-middle-ages-medieval-antiquity-economic-theory-history-capitalism. As Tedesco writes, critiquing the brilliant Marxist historian Perry Anderson’s work on the transitions from antiquity/slavery to feudalism/serfdom, and capitalism/wage labor: “The Marxist schema …misleads…It depicts historical transitions as if they were characterized by successive, clearly demarcated modes of surplus appropriation, progressing from slavery in the ancient world to serfdom in the Middle Ages and wage labor in capitalist societies. In reality, the ways in which the possessing classes extracted a surplus from the direct producers were much more volatile and contingent than this model suggests. We cannot find evidence to support this traditional picture if we move from abstract models to a detailed interrogation of ancient and medieval sources on the ground. It is equally erroneous to suppose that there is a necessary association between serfdom and the feudal system. Feudal systems existed outside of Western Europe as well as inside it, and serfdom was not the defining social structure in every such society — India and China were significant exceptions, for instance. Finally, wage labor is not unique to capitalist societies, having been common in the ancient and medieval worlds as well. On the other hand, we can find many examples of slavery and indentured labor being deployed under capitalism, from the giant plantations of pre-revolutionary Haiti or the southern United States to the savage exploitation of migrant workers in the Gulf monarchies today.”

5. I am referencing two magisterial books by the brilliant Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Capital, 1845-1875; The Age of Empire, 1875-1914.

5A. Bob Avakian, Breakthroughs: The Historic Breakthrough of Marx and Further Breakthroughs with the New Communism (Chicago: Insight Press, 2019), p. 16.

5B. Avakian, Breakthroughs, p. 6.

6. That’s what Engels was getting at in this part of his graveside speech: “Just as Darwin discovered the law of development of organic nature, so Marx discovered the law of development of human history: the simple fact that…the production of the immediate material means, and consequently the degree of economic development attained by a given people or during a given epoch, form the foundation upon which the state institutions, the legal conceptions, art, and even the ideas on religion, of the people concerned have been evolved, and in the light of which they must, therefore, be explained, instead of vice versa, as had hitherto been the case.”

6A. Avakian, Breakthroughs, p. 17: “A lot of people say, ‘Oh, Marx, he’s all about the class struggle. He thought he did a big thing by discovering that classes exist and classes struggle.’” In fact, Avakian notes, Marx in and 1852 letter to Joseph Wedemeyer, explained that “this was not the essence, and the importance, of what he did that was new—it went far beyond merely speaking to the existence of classes and class struggle.”

7. For brilliant discussions of organization/anarchy as the main driving contradiction of capitalism, see Avakian, Breakthroughs, pp. 33-34, and Raymond Lotta, “On the Driving Force of Anarchy and the Dynamics of Change” (2013).

7A. Trusty Wikipedia does a decent job on “Marx’s theory of alienation”:

“Marx's theory of alienation describes the separation and estrangement of people from their work, their wider world, their human nature, and their selves. Alienation is a consequence of the division of labour in a capitalist society, wherein a human being's life is lived as a mechanistic part of a social class. The theoretical basis of alienation is that a worker invariably loses the ability to determine life and destiny when deprived of the right to think (conceive) of themselves as the director of their own actions; to determine the character of these actions; to define relationships with other people; and to own those items of value from goods and services, produced by their own labour. Although the worker is an autonomous, self-realised human being, as an economic entity this worker is directed to goals and diverted to activities that are dictated by the bourgeoisie—who own the means of production—in order to extract from the worker the maximum amount of surplus value in the course of business competition among industrialists. The theory, while found throughout Marx's writings, is explored most extensively in his early works, particularly the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, and in his later working notes for Capital, the Grundrisse” [and with Engels, The German Ideology (1845) - PS].

8. See Marx and Engels, Communist Manifesto, pp. 72-73: “in proportion as the exploitation of one individual by another is put an end to, the exploitation of one nation by another will be put an end to. In proportion as the antagonism between classes within the nation vanishes, the hostility of one nation to another will come to an end.” Twenty-three years later, Marx would hail the Paris Commune as “the bold champion of the emancipation of labor, emphatically international…the Commune annexed to France the working people of all the world…The Commune made a German working man its Minister of Labor…The Commune admitted all foreigners to the common cause of dying for an immortal cause…[and] honored the heroic sons of Poland by placing them at the head of the defenders of Paris …[and] pulled down that colossal symbol of [national and] martial glory, the Vendome column.” Marx’s Civil War in France ended by identifying the International Working Man’s Association (the First International) as “nothing but the international bond between the most advanced working men in the various countries of the civilized world.” Marx, Civil War in France, pp. 77-78, 98.

9. Karl Marx, Critique of the Gotha Program (1875).

10. Marx and Engels, Communist Manifesto, p. 75.

11. Marx, The Civil War in France, p. 73.

12.. Marx, The Civil War in France, p. 73.

13. Communist Manifesto, 74

14. Communist Manifesto, 73.

15. Marx and Engels, Communist Manifesto, p.55.

16. Communist Manifesto, 86.

17. Quoted in Avakian, Breakthroughs, p. 16.

18. Communist Manifesto, 64.

I should go read Marx instead of looking for your typos.

I did order Luke Epplin’s baseball book that you recommended a week or so ago.

In the paragraph after writing that the third mistake doesn’t concern us: “They was shot….”

Under Point 12: “If this seems.”

I appreciate your erudite discussion of Marxism.